On Wednesday, July 19, the European Parliament voted in favor of a major new legal framework regarding cybersecurity: the Cyber Resilience Act (CRA).

According to the press release following the vote:

"The draft cyber resilience act approved by the Industry, Research and Energy Committee aims to ensure that products with digital features, e.g. phones or toys, are secure to use, resilient against cyber threats and provide enough information about their security properties."

This choice of examples, mundane as they may seem, subtly underscores a critical debate surrounding the CRA: its broad scope of application. While some may question the inclusion of such commonplace items, it reflects the Act's comprehensive approach to cybersecurity.

The CRA's introduction is timely and vital. It represents a concerted effort to enhance the resilience of digital products against cyber threats, demanding international collaboration and strategic foresight. This initiative is a significant stride in bolstering EU's cyber defense and asserting its digital sovereignty.

For context, the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) highlights a concerning escalation in both the frequency and complexity of cyberattacks targeting the EU, as detailed in their Threat Landscape report. Public administration, constituting approximately 19% of these attacks, emerged as the most vulnerable sector in 2022 and 2023.

Decoding the Cyber Resilience Act: How Will It Work?

The CRA's main objective is to establish a universal cybersecurity baseline for all products with digital components sold within the EU. This encompasses a wide array of items, from software and network-connectable devices to items containing embedded computing systems. Significantly, the Act does not differentiate between consumer and enterprise-grade products.

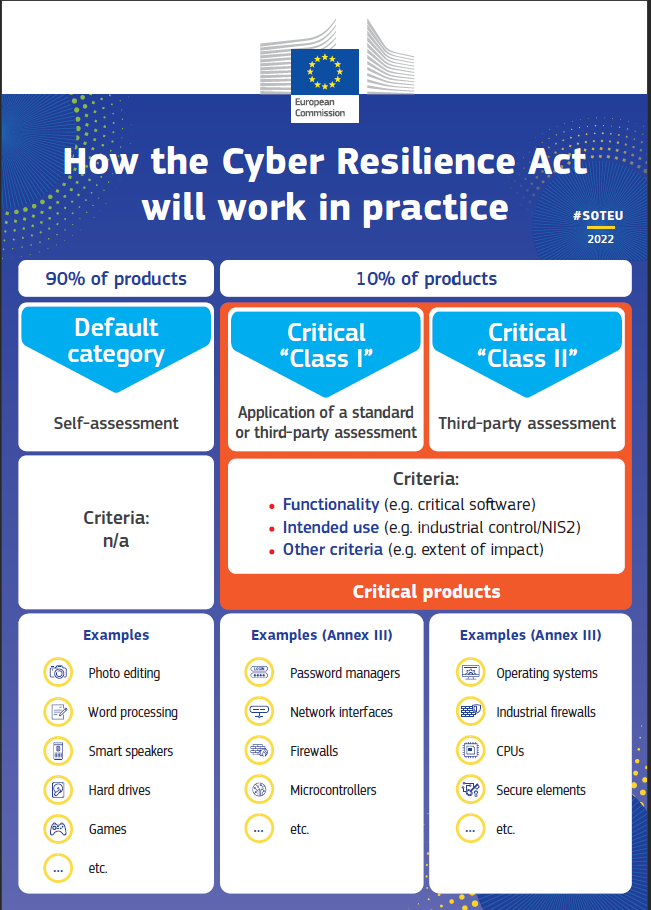

To manage this diverse range of products, the Act proposes a categorization into three security tiers: the default category, critical "Class I", and "Class II". According to the EU Commission, it is anticipated that a majority (around 90%) of products will fall under the 'default category'.

Based on this product categorization, the CRA introduces differentiated levels of security assessments. Most notably, "critical software" demands rigorous third-party evaluation. However, the categorization's scope is not always straightforward. Consider the example of hard drives: while generally classified under the default category, ambiguity arises when these hard drives are employed in cloud data centers handling sensitive data. This grey area highlights the need for more nuanced guidelines within the Act.

One aspect of the CRA that stands out is its stringent approach to enforcement through substantial financial penalties. Vendors operating in the EU single market face fines up to €15 million or 2.5% of their global revenue for non-compliance. This measure reflects a shift in perspective, treating security as a fundamental, non-negotiable aspect of product development, rather than a secondary consideration.

This emphasis on financial accountability is a strategic move by the EU. By assigning a tangible cost to cybersecurity risks — costs that some companies have historically been willing to absorb — the CRA aims to recalibrate the risk-reward equation in favor of enhanced security measures.

But this raises another fundamental question: who in the supply chain should be held accountable? Or said differently, who bears the risk?

Who Bears the Risk? The CRA's Stance on Responsibility

The CRA is unequivocal in assigning responsibility for digital product security: the onus lies with the manufacturers. In cases where the manufacturer and software producer are the same, this is straightforward. However, the act enters murky waters when it comes to open-source software. Defining security ownership for code written by one and reused by another presents a complex challenge.

As a reminder, open-source is a pillar of modern software. It typically accounts for 70% to 90% of code in Web and cloud applications — application security firm Synopsys found that 98% of applications analyzed using its service included open-source software, and 75% of the average codebase came from open-source projects. They also found that, on average, a software application relied on more than 500 open-source dependencies.

This underscores the significant challenge faced by nearly every commercial business in conducting necessary due diligence. They should ensure that all open-source components have been accurately evaluated.

Reactions from the Open-Source Community

The primary worry comes directly from the open-source community itself. Many prominent open-source projects express concern because the Cybersecurity Act appears to suggest that the responsibility of compliance should fall on the shoulders of open-source developers. This implies that if any commercially sold software in the EU market incorporates an open-source component, its creators could be held accountable for its security.

This literal interpretation could potentially create an unsustainable situation for those contributing to open-source projects.

However, it's important to note that the CRA does specifically exempt open-source software that is developed or supplied outside of commercial activities. The issue, though, seems to lie in how the CRA defines open-source activity. The act seems to be permeated with the notion that most open-source activity stems from "benevolent work," a perspective that is largely considered out-of-date in today's context.

As an example, projects receiving donations or with corporate contributors would not be considered benevolent work and fall under the act's purview. But this view couldn't be further from the reality: open-source and commercial activities are often intertwined in complex hybrid operating profiles. Many open-source companies are developing open-source products with permissive licenses, while they monetize their activity through the selling of support services and premium features.

Conversely, it is not uncommon for tech giants to employ full-time engineers to work exclusively on some of the biggest open-source projects.

This highlights a significant misalignment between EU lawmakers and the open-source community. Key players in the open-source field, such as OpenSSF and the Debian Foundation, have criticized the legislators for failing to consult them during the drafting of the act.

The Future of Open-Source Under the CRA

Despite prevailing concerns, it's unlikely that the Cyber Resilience Act will signal the end of open-source software in the European Union. It's true that current versions of the CRA, don't explicitly define its scope. However, this doesn't preclude the possibility of future amendments.

The potential upheaval caused by mandating every software producer to scrutinize all its open-source components is simply too vast. We anticipate that the largest industry enterprises in the single market, all heavily reliant on software, will wield their considerable lobbying power to influence the law in their favor upon recognizing the potentially catastrophic impact. The stakes are too high, and the risk of damaging Europe's competitive edge is enormous.

Even if these efforts fail, there may well be grounds to challenge the law in court due to the ambiguities present in the text. Consequently, we can expect to see the language of the law refined in the coming months. Ideally, this will occur through close collaboration with leading open-source organizations.

Conclusion: A Regulatory Milestone with Challenges Ahead

The Cybersecurity Act (CRA) represents a significant milestone in the European Union's (EU) regulatory evolution, with the goal of unifying cybersecurity standards across its market. More than just a regulatory measure, the CRA is a political statement, intentionally timed to demonstrate the EU's commitment to combating cyber threats. The Act's broad scope and rapid implementation schedule can be largely attributed to the current geopolitical turbulence.

The CRA enforces security measures throughout a product's lifecycle, compelling manufacturers to prioritize cybersecurity. This bold move is essential for enhancing digital security within the EU. However, the Act's wide scope and numerous ambiguities have also created concerns. Are the fears of open-source organizations bearing the burden of security responsibility justified?

While it is ultimately up to you to form an opinion, we believe that these fears are not entirely justified, although there is some uncertainty. The existence of legal gaps and the potentially significant consequences for the EU economy if the law is strictly enforced in its current state are valid arguments for future refinements. These refinements should aim to enhance, rather than impede, the innovation and resilience that open-source technology brings to the digital landscape. However, achieving this will require vigilance.

In conclusion, the Cybersecurity Act represents a crucial step towards a more secure digital environment in the EU. While challenges and ambiguities exist, it is essential to strike a balance that encourages innovation while ensuring robust cybersecurity measures.