In recent years, more and more companies have launched bug bounty programs as proof of their commitment to security and as a way to implement continuous monitoring of their corporate attack surface. Those programs sometimes offer generous payouts to vulnerability reporters, and often partner with dedicated platforms that offer various services such as:

- Payment and billing management

- Triaging as a Service

- Investigation assistance

Platforms rely on a “hacker community”, a group of people who hack on the programs to discover vulnerabilities and earn bounty money. Most of those “hackers” are self-employed in a way that allows them to comply with local applicable tax laws.

Bug bounty programs are a great way to have a corporate perimeter or set of applications audited by a large set of people, nearly continuously. They can be a great addition to a company’s security policy. In fact, GitGuardian has been running a bug bounty program for multiple years, as a complement to our periodic audits and overall security strategy.

Bug Bounty Done Wrong

The problem with bug bounty programs starts when they try to substitute for a proper Vulnerability Disclosure Policy. When they do, they no longer improve your security posture; they undermine it.

Bug bounties, by design, are selective. From a ”hacker” perspective, they come with limited scopes, opaque triage processes, gatekeeping platforms, or even eligibility requirements. As a result, valid, good-faith vulnerability reports can get ignored, rejected, or buried – not because they lack accuracy or merit, but because they fall outside of the boundaries of the programs’ terms or the opaque decision of a third-party triager. Payout levels also undermine this testing model, turning continuous monitoring into a blind spot shaped by market incentives; why search for or report vulnerabilities when they pay little or nothing?

Using a bug bounty platform as the only possible communication channel for vulnerability disclosure creates unnecessary friction:

- Mandatory registration forces researchers to trade their privacy for participation.

- Non-disclosure clauses can silence conversation about systemic risks, and more generally hinder information sharing.

- Platform gatekeeping can discourage reporters.

- Worse: out-of-scope dismissals allow serious vulnerability reports to be voided, and never reported to security teams

These blind spots don’t make an organization more secure. They make it easier to overestimate the security posture, thinking that fewer reports mean fewer problems.

A good Vulnerability Disclosure Policy (VDP) should promote openness. It should be a clear and accessible way for anyone – a professional researcher, a student, or a concerned user – to report a security issue safely, privately, and without process complexity. A good disclosure policy should enable communication rather than controlling it.

One particular issue that highlights how bug bounty can fail as a disclosure channel lies in how they handle secret leak reports.

GitGuardian’s experience

One of the core foundations of GitGuardian is the detection and remediation of secrets leaked in public spaces. Over the course of the past year, while working on improving our understanding of the secret sprawl issue, we performed responsible disclosures to hundreds of companies.

GitGuardian’s cybersecurity research team is not a bug bounty crew. We do not seek any reward for reporting incidents. For this reason, we usually attempt to contact affected companies directly, preferably via email, and sometimes through online forms dedicated to security incident reporting. We only fallback to the bug bounty program channel as a last resort, or when directly prompted to do so.

While working with platforms, we experienced a variety of situations and answers that illustrate how bug bounty can fail as a disclosure channel.

400 PoC or GTFO

As a result of a large-scale research project, we recently reported leaked private keys related to valid X. 509 certificates. The risk of such incidents can generally be considered high, as a leaked key can be used to set up Man-In-The-Middle attacks against the company’s public assets. Some of our reports had to go through bug bounty platforms, which already create friction. As much as we can automate the sending of hundreds of e-mails, filling bug bounty reports at scale is challenging.

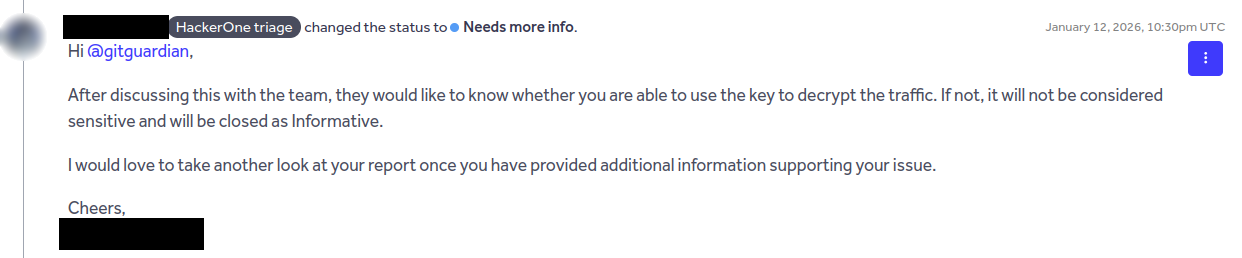

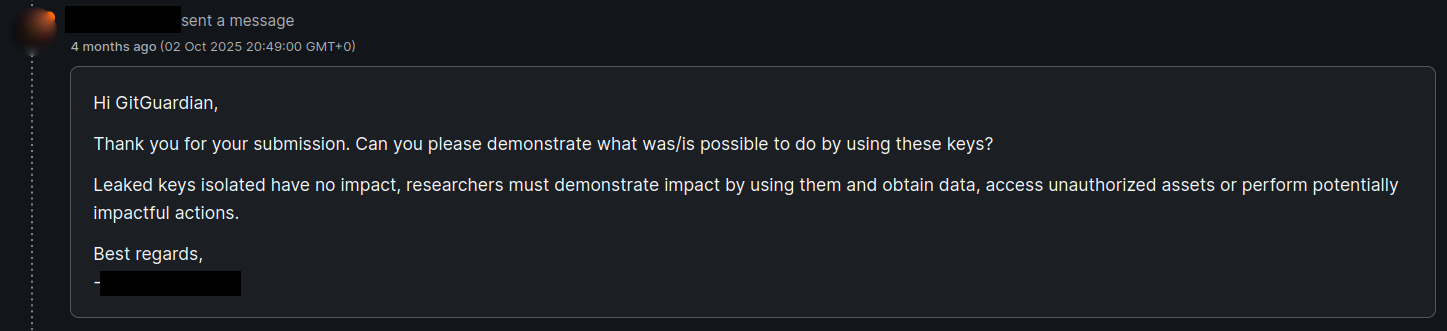

In all our reports, the triagers asked for a proof of concept exploitation.

First, proving a credential's impact has a clear ethical boundary: demonstrate the potential for harm without causing actual harm. This means verifying credentials are valid, confirming what resources they access, and documenting their privilege level, but without reading production data, modifying systems, or performing harmful actions. This is not always possible, depending on the credential type. In the case of leaked X.509 certificate private keys, creating such a proof-of-concept would have required decrypting real traffic or impersonating production services — crossing from validation into active attack — which could have severe legal consequences

Then, the main question is: what happens after the report gets closed as informative? There is a chance that no action will be taken. In some cases, the issue might never pass the triaging filter and reach the corporate security team.

In our case, most reports were actually closed as informative, and none of the related certificates were revoked. Worst of all, some GitHub repositories containing leaked private keys have never been deleted. We later contacted the related certificates’ issuer authorities to have the keys black listed and certificates revoked.

403 Private Program

Bug bounty programs can either be public or private. Public programs can be viewed, accessed, and interacted with by anyone. On the other hand, private programs are invite-only, so only selected members of the platform's community can report vulnerabilities.

In that case, obviously, the program can not be considered a proper disclosure channel. However, there is a reporting flow that overlooks this issue:

- You discover a vulnerability and attempt to report it through standard channels (security@, contact forms).

- You receive a response: 'Please submit via our Bug Bounty Program.'

- You navigate to the platform, only to find it's private and invitation-required.

- Without an invitation, you hit a dead end with no alternative channel.

Our team has faced this situation once, making the reporting process painful and highlighting how companies often lack awareness about vulnerability disclosure practices.

Similarly, a documented program can have expired or been decommissioned. In this case, the communication channel is effectively nonexistent. This was the case when we reported a leaked API key to xAI in 2025.

404 Secret Not Found In Scope

The scope of a program includes the list of assets that are authorized to be worked on. It also includes the list of vulnerabilities that are accepted in reports. The purpose of this restriction is to limit the number of low-quality reports or reports for vulnerabilities that are widely recognized as lacking real-world impact.

However, if the scope of a program is too restricted, valid and severe issues might get discarded by the triaging team without further notice. In that spirit, we faced bug bounty programs that explicitly marked leaked credentials as out of scope. The platforms sometimes even encourage their customers to ban secrets. The reason behind this is tied to the origin of the credentials, as we discussed with a platform representative:

We strongly advise our clients to exclude leaked secrets from their bug bounty program scope. The reality is that compromised credentials frequently originate from illicit sources. There's a thriving underground market for stolen credentials, and by offering bounties for leaked secrets, we risk inadvertently incentivizing and legitimizing a secondary marketplace for compromised authentication data.

While this concern is understandable, excluding leaked secrets creates a dangerous blind spot. Valid credentials represent immediate security risks: unauthorized access, data breaches, or compromised systems.

The solution isn't to ban secret reports—it's to require source transparency. Researchers should disclose where the credentials were found. This approach enables security teams to investigate the leak's origin and take appropriate remediation action, while distinguishing legitimate research from illicit activity.

500 Triager error

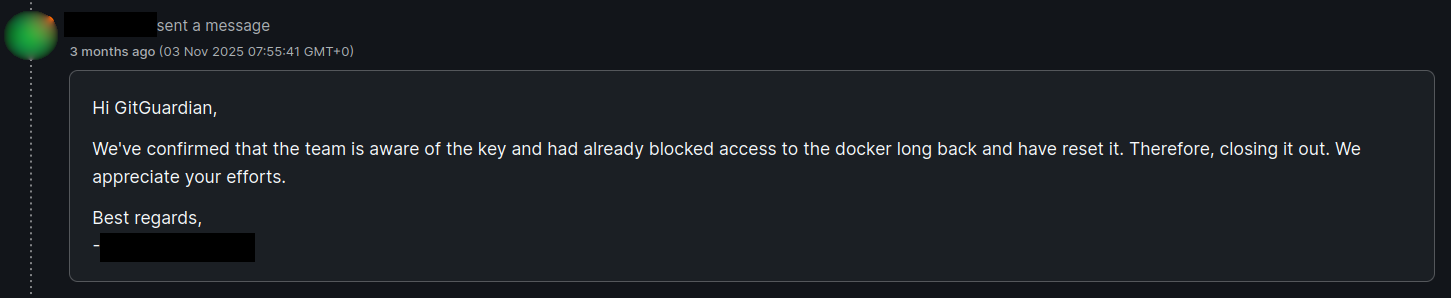

Triager gatekeeping can also be an issue in case of a misunderstanding about a security issue. While misunderstandings can occur with corporate security teams, triagers can close the communication channel when they deem an issue uninteresting. While it is often possible to ask to reopen closed reports or ask for mediation, this can prevent legitimate reports from reaching the corporate teams and create unnecessary friction.

In the above case, the triager closed the issue while the affected credentials were still valid. Such behaviors create frustration, discourage reporters and, again, prevent secrets from being reported.

302 Redirect To Bug Bounty

Even when a direct communication channel with corporate security teams exists, it happens that those teams redirect mailed reports to a bug bounty platform. The rationale is understandable: centralizing all vulnerability reports in one place simplifies triaging and tracking.

Doing so not only slows the remediation process down, but also creates a dangerous bottleneck as the submission will likely have to comply with the bug bounty rules and scope definition, with the same pitfall as issues directly reported on platforms..

It also goes against the potential privacy requirements of the reporter, who would have to create an account on the bug bounty platform and sometimes even fill out tax regulation documents.

We received such a response when we contacted xAI for a leaked token last year. In that case, the corporate team also fixed the issue in the background, even before we could submit it to their program, demonstrating a clear lack of transparency.

Dear Gaëtan,

Thank you for your email.

For us to analyze and also for you to receive proper credit, if applicable, would you please submit this to xAI's Bug Bounty Program on HackerOne?

https://hackerone.com/x?type=team

Thanks!

xAI Team

Vulnerability Disclosure Policy done right

Writing a clear Vulnerability Disclosure Policy that provides an open and transparent communication channel is of prime importance to ensure your company receives vulnerability reports properly. As we explained above, such a policy should promote openness, transparency, and reporters’ safety. Privacy is also a core concept of any proper VDP and should be emphasized, as is explained in documents from the US Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency:

How should my agency treat vulnerability reports from anonymous sources?

These reports should be treated the same as all other reports: like a gift. Knowing the source of a report can be a real benefit because it allows for rapport to develop. However, if the person who submits a report isn’t known, the claim should simply be evaluated on its merits – like every other report.

When bug bounty platforms are your only security communication channel, such privacy can not be appropriately granted to vulnerability reporters.

In fact, CISA published a complete template for Vulnerability Disclosure Policy that emphasizes those openness and transparency concepts. The document is meant to be a regulatory requirement for government agencies, but it can be used as a basis to write the VDP of any company.

At GitGuardian, we are not against bug bounty programs, as we think they can be a great addition to a company’s security policy. However, it is of prime importance to understand the limits and blind spots created by those platforms.

Most importantly, bug bounty programs must complement—not replace—a public Vulnerability Disclosure Policy. Private, invitation-only programs create insurmountable barriers for new researchers and should never be the sole disclosure channel. Companies should maintain accessible public VDPs alongside any BBP, with clear escalation paths that allow critical reports to bypass platform restrictions when necessary. Direct reports to security@ should remain direct—triaged by internal teams who understand the full context of their infrastructure, not filtered through external platform scopes that may dismiss legitimate threats on technicalities.

Especially, if you manage a bug bounty program, make sure to include leaked credentials in its scope. Credentials-based attacks have become the number one cyber threat in the modern world, so those incidents should not be disregarded. Asking and verifying the source of the leaks will allow better investigation of the leak issue while reducing the risk of buying stolen credentials from the black market.

To conclude, whatever communication channel you choose for your vulnerability reports, make sure to promote it and make it as visible as possible, for example, with an RFC 9116 security.txt file. There is nothing worse than a communication channel no one knows about.