- OpenID Connect (OIDC) simplifies user auth, but shifts the security burden to secrets management and token validation logic.

- A common critical failure is treating Client Secrets as configuration rather than high-value credentials, leading to hardcoding secrets.

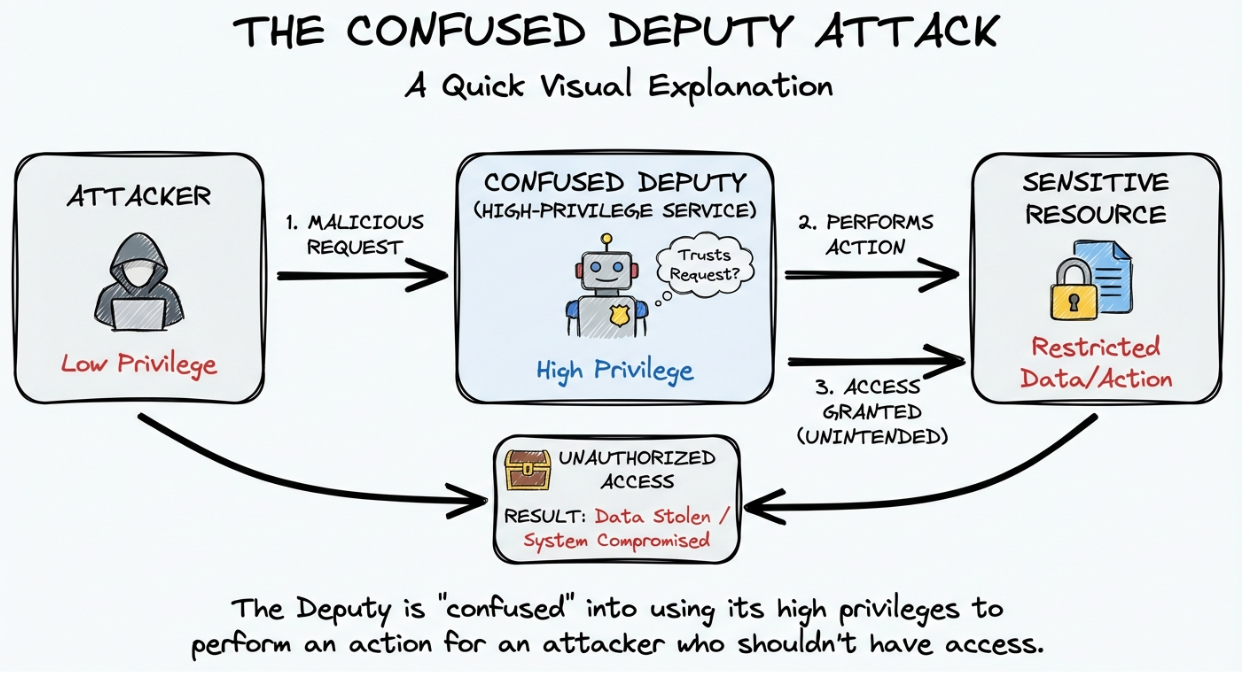

- Incomplete JWT validation (ignoring aud or iss claims) leaves applications vulnerable to "Confused Deputy" attacks.

- As Non-Human Identities (NHIs) and Workload Identity Federation rise, OIDC misconfigurations in CI/CD pipelines are becoming a primary attack vector.

Most developers integrate OpenID Connect assuming the hard part is over once the IdP handles authentication. But a forgotten client_secret in a Docker Compose file or a bypassed audience claim validation, and their "secure" login flow becomes an attack vector.

OIDC is fantastic, but misimplementing it creates the biggest risk of all: a false sense of security.

By building on OAuth 2.0, OIDC standardizes identity exchange using JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) and eliminates password management. Delegate authentication to Okta, Auth0, or Azure AD, and you never hash another password. But while OIDC solves the password problem, it transforms the secrets problem. The IdP handles the cryptography, but developers still control the integration code, and that's where the vulnerabilities hide.

OIDC integrations have their security best practices: handling high-value secrets (Client Secrets), configuring sensitive trust boundaries (Redirect URIs), and validating complex artifacts (ID Tokens). This guide explores the specific security pitfalls developers face when implementing OIDC, focusing on secrets management, token hygiene, and the rising risks of Non-Human Identities (NHIs).

Client Secret Leaks

In the standard OIDC Authorization Code flow (used by most server-side web apps), the application exchanges an authorization code for an ID Token and Access Token. To do this, the application must authenticate itself to the IdP using a client_id and a client_secret.

The client_id is public information. The client_secret is effectively a password for your application.

Yet despite its name, we constantly see client_secrets treated as non-sensitive configuration data. They appear in:

docker-compose.ymlfiles committed to source control.- Hardcoded variables in frontend JavaScript bundles (where they are visible to anyone via "View Source").

- Unencrypted environment variables in CI/CD logs.

You don't have to look far to find examples of leaks. In October 2025, a critical vulnerability (CVE-2025-59363) in OneLogin's API exposed the plaintext client_secret of every OIDC app in affected tenants. While this was a provider flaw, it proves that static secrets are single points of failure.

If an attacker gains your client_secret, they can impersonate your application. Depending on the scope of the compromised app, they could phish users, trigger downstream actions, or, in the case of service-to-service OIDC, gain full administrative access to backend resources.

Three non-negotiable rules for production OIDC implementations:

- Never include a Client Secret in a native mobile app or Single Page Application (SPA). Use PKCE (Proof Key for Code Exchange) instead, which eliminates the need for a static secret.

- For server-side apps, store Client Secrets in a dedicated secrets manager (HashiCorp Vault, AWS Secrets Manager).

- Monitor your repositories for accidental commits of strings matching standard OIDC secret patterns (e.g.,

sk_live_,GOCSPX-) using GitGuardian.

Protecting this secret is step one. Step two is ensuring that even with a valid secret, your application only accepts tokens intended for it. This is where most OIDC integrations fail.

Signature Verification ≠ Validation

The most technical pitfall in OIDC implementation is improper token validation. When an app receives an ID Token (a JWT), it looks like a cryptic string. It is tempting to simply decode it (using jwt.decode()) to extract the user's email or name.

But decoding is not validation!

If you do not strictly validate the token claims, a malicious user could get a valid token from the same IdP but intended for a different application (perhaps one they control) and present it to your backend. If your backend only checks "Is this token signed by Google?", it would accept it.

This is the "Confused Deputy" attack:

A robust OIDC implementation must enforce the following validation logic on every ID Token:

- Signature Verification: Is the token signed by the IdP's private key? (Fetch public keys via the JWKS endpoint).

- Issuer (

iss) Check: Does the token come from the expected IdP (e.g.,https://accounts.google.com)? - Audience (

aud) Check: This is the critical step. Theaudclaim must match your specificclient_id. This proves the token was issued specifically for your app, not just any app using that IdP. - Expiration (

exp) Check: Is the token still valid?

Do not write your own validation logic. Use battle-tested libraries (like Authlib or node-jose) but ensure you explicitly configure the expected audience. Many libraries default to skipping the audience check if the parameter is not provided.

Mini-Tutorial: Validating JWTs with Authlib (Python)

To demonstrate robust JWT validation in Python, we'll use Authlib, a popular library that implements OAuth 2.0 and OpenID Connect specifications. This short example focuses on the critical steps discussed above.

Installation:

pip install Authlib

- Prepare Your Public Key & Token: In production, fetch the public key (JWK) from your IdP's

.well-known/jwks_uriendpoint. For this example, we'll use a placeholder structure.

`from authlib.jose import jwt, JsonWebToken`

`import requests`

`# Production: Fetch JWK from IdP's discovery endpoint`

`# discovery = requests.get("https://idp.example.com/.well-known/openid-configuration").json()`

`# jwks = requests.get(discovery["jwks_uri"]).json()`

`# jwk = [k for k in jwks["keys"] if k["kid"] == token_kid][0]`

`# Example: JWK structure (DO NOT use these placeholder values in production)`

`jwk = {"crv": "P-256", "kty": "EC", "alg": "ES256", "use": "sig", "kid": "example-key-id", "x": "<fetch-from-idp>", "y": "<fetch-from-idp>"}`

`# The JWT string you received`

`jwt_token_string = "eyJhbGciOiJFUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCIsImtpZCI6InlhZC4uLiJ9.eyJpc3MiOiJodHRwczovL2lkcC5leGFtcGxlLmNvbSIsImF1ZCI6ImFwcC1jbGllbnQtYWwiLCJleHAiOjE2NzIyNDU4MjIsImlhdCI6MTY3MjI0MjIyMn0.ey..."`

- Decode and Validate Claims (including

audandiss): Thejwt.decode()method automatically verifies the signature, but signature verification alone is not sufficient validation. We must also validate the claims usingclaims_optionsto enforceissandaudchecks, preventing "Confused Deputy" attacks. We also explicitly configure the accepted algorithm usingJsonWebTokento prevent algorithm 'none' attacks.

`# Define required claims and their expected values`

`claims_options = {`

`"iss": {"essential": True, "value": "https://idp.example.com"}, # Expected Issuer`

`"aud": {"essential": True, "value": "app-client-a"} # Expected Audience (YOUR client_id)`

`}`

`# Restrict accepted algorithm to prevent 'none' attacks`

`jwt_validator = JsonWebToken(["ES256"]) # Explicitly allow only ES256`

`try:`

`claims = jwt_validator.decode(jwt_token_string, jwk, claims_options=claims_options)`

`claims.validate() # Explicitly validate expiration and not-before claims`

`print("JWT is valid! Claims:", claims)`

`except Exception as e:`

`print(f"JWT validation failed: {e}")`

This snippet provides a robust starting point for secure JWT validation, covering signature, issuer, audience, expiration, and algorithm checks. Always ensure your JWK is fetched securely from the IdP's .well-known/openid-configuration endpoint.

These validation rules apply to human authentication. But the fastest-growing OIDC attack surface isn't users logging in, but rather services authenticating to each other.

OIDC for Non-Human Identities (NHIs)

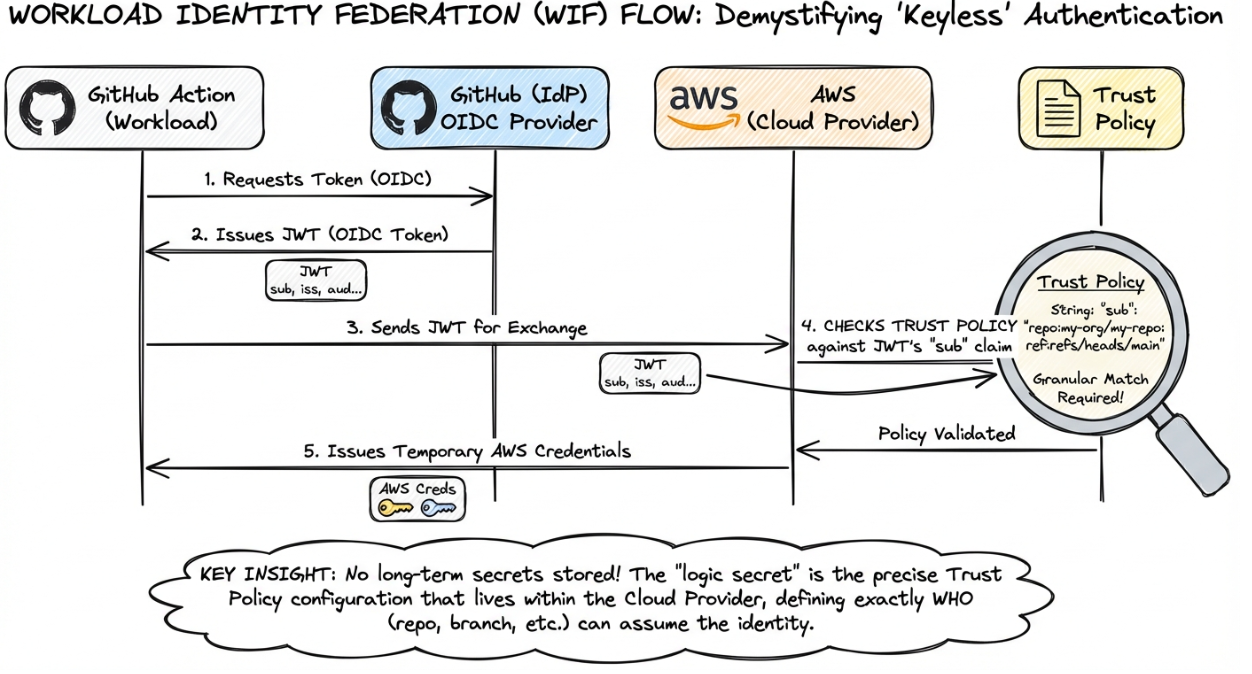

The frontier of OIDC usage (and risk) is no longer just human login: it is Workload Identity Federation.

Traditionally, if a GitHub Action needed to deploy to AWS, you would create a long-lived AWS Access Key and store it as a GitHub Secret. This created a static credential management nightmare.

The modern pattern uses OIDC. GitHub acts as the OIDC Identity Provider. AWS acts as the Relying Party.

- The GitHub Action requests a JWT from GitHub.

- The Action sends this JWT to AWS.

- AWS validates the token and exchanges it for temporary cloud credentials.

This creates a keyless authentication flow. However, it introduces a new kind of "logic secret" in the form of the Trust Policy.

The "Sub" Wildcard Pitfall

This flow is only as secure as how restrictively the cloud provider checks the sub (subject) claim of the incoming token.

A secure policy looks like this:

Allow if sub == "repo:my-org/my-repo:ref:refs/heads/main"

A vulnerable policy looks like this:

Allow if sub LIKE "repo:my-org/*"

An attacker who can create a branch or fork within my-org can now trigger workflows that AWS will trust with production credentials. This isn't theoretical: in 2024, researchers demonstrated this exact attack pattern against misconfigured GitHub Actions OIDC integrations, gaining temporary AWS credentials with administrative scope.

If developers configure overly permissive trust policies (wildcarding the branch or the repo), they effectively grant cloud access to any workflow running in the organization, including those on insecure test branches or forked repositories.

In the world of NHIs, the OIDC Trust Policy is the new secret. It doesn't look like a password, but if it leaks or is misconfigured, the impact is identical to a leaked admin key.

Production Deployment: Securing the Chain

OIDC requires ongoing operational vigilance. Identity configuration is part of the secrets lifecycle, not a one-time setup task.

- Centralize Redirect URIs: The

redirect_uriis an allowlist of where the IdP is allowed to send tokens. Avoid wildcards. An attacker who finds an open redirect on your domain combined with a wildcardredirect_uriconfiguration can steal auth codes and tokens. - Rotate Secrets Regularly: Just because it's a "Client Secret" doesn't mean it should live forever. Establish a rotation policy for OIDC credentials just as you would for database passwords, a key step in moving up the Secrets Management Maturity Model.

- Audit .well-known Configurations: Ensure your application is using the discovery endpoint (

.well-known/openid-configuration) dynamically to fetch keys. Hardcoding public keys or endpoints leads to outages when the IdP rotates their infrastructure.

Conclusion: Identity is the New Perimeter

The shift to OIDC doesn't eliminate secrets management. User passwords become Client Secrets. Session tokens become JWTs with validation requirements. Static API keys become Trust Policies that act like access control logic.

Secure identity starts with recognizing that every OIDC integration introduces new secrets to protect, new validation logic to enforce, and new attack surfaces to monitor. The IdP handles cryptography. You handle everything that happens when those tokens reach your application.

That's where most breaches happen.

Further Reading & Developer Tools

To go beyond the basics and audit your own implementation, we recommend these technical resources:

- OIDC Playground: An invaluable interactive sandbox for debugging. It allows you to step through every stage of the OIDC flow to inspect the structure of HTTP requests, responses, and token artifacts in real-time.

- Scott Brady’s Identity Blog: For developers who need to understand the "why" behind the specs. Scott’s deep dives into OAuth 2.0 and OIDC security cover complex edge cases and specific library misconfigurations that standard documentation often misses.

- Curity: The Token Handler Pattern: If you are building Single Page Applications (SPAs), this is essential reading. It details why storing tokens in the browser is dangerous and provides a complete architectural guide for implementing the "Backend for Frontend" (BFF) pattern to keep secrets secure.

FAQ

What is the difference between OAuth 2.0 and OIDC?

OAuth 2.0 is a framework for authorization (granting access to resources). OIDC (OpenID Connect) is a layer built on top of OAuth 2.0 specifically for authentication (verifying user identity). OIDC adds the ID Token (a JWT containing user info) to the standard OAuth flow, enabling applications to verify who the user is, not just what resources they can access.

Why is the Audience (aud) check so critical in OIDC?

The aud claim identifies the intended recipient of the token. Without verifying it, your application accepts any valid token issued by the Identity Provider (IdP). This allows an attacker to take a token issued for their own malicious app (validly signed by Google/Okta) and use it to impersonate a user on your app. This is known as the "Confused Deputy" problem, where a legitimate token is misused in an unintended context.

Should I commit my OIDC Client ID to my repository?

Generally, yes. The client_id is public information and is exposed in the URL during the authentication flow. However, the client_secret is highly sensitive and must never be committed. Use environment variables or a secrets manager to inject the secret at runtime. The client ID alone cannot grant access—it requires the corresponding client secret for authentication, which must remain protected.

How does OIDC help with Non-Human Identity (NHI) security?

OIDC allows for "keyless" authentication via Workload Identity Federation. Instead of storing long-lived API keys (secrets) in CI/CD platforms like GitHub Actions, the platform issues a short-lived OIDC token. The cloud provider (AWS/Azure/GCP) validates this token against a Trust Policy to grant temporary access. This eliminates the risk of static credential leakage, provided the Trust Policy is scoped correctly with appropriate conditions on subject, repository, and environment claims.

What is the risk of using "Implicit Flow" in OIDC?

The Implicit Flow returns tokens directly in the URL fragment, where they are vulnerable to history logging, referrer leakage, and browser manipulation. This flow is now considered deprecated for most use cases due to these inherent security weaknesses. Developers should use the Authorization Code Flow with PKCE (Proof Key for Code Exchange) for both mobile and web applications to ensure tokens are exchanged securely through the back channel rather than exposed in URLs.