- Learn practical strategies for generating, rotating, and storing session keys, self-use keys, and pre-shared keys.

- Avoid common pitfalls like key reuse, improper storage, and logging sensitive material.

- Follow best practices for secure key generation, aggressive rotation, and vault integration to minimize risk and maintain compliance.

Symmetric cryptography powers everything from HTTPS to JWT tokens, but key management remains a significant challenge. This developer guide covers three critical use cases—session keys, self-use keys, and pre-shared keys—with practical strategies for secure generation, rotation, and storage.

Understanding Cryptographic Fundamentals

Cryptography often intimidates developers due to its mathematical complexity, yet it forms the backbone of modern computer security—from HTTPS connections to payment processing. While you don't need a mathematics PhD to work with cryptography, understanding its core principles is essential for any IT professional.

Cryptography serves four primary security objectives:

- Integrity: Ensures data hasn't been tampered with during transmission or storage

- Confidentiality: Restricts data access to authorized parties only

- Authenticity: Verifies the sender's identity and the intended recipient

- Non-repudiation: Prevents parties from denying their involvement with specific data

These objectives are achieved through three fundamental cryptographic primitives:

- Encryption algorithms provide confidentiality

- Hashing functions ensure integrity (among other things)

- Digital signatures establish authenticity and non-repudiation

These primitives combine to create comprehensive security protocols like TLS, which secures web communications. The critical component that makes all these algorithms work is the management of cryptographic secrets—the keys that ensure security.

The Tale of Two Cryptographic Approaches: Symmetric vs Asymmetric Cryptography

Cryptographic algorithms fall into two distinct categories: symmetric and asymmetric. The key difference lies in how they handle cryptographic keys.

Symmetric cryptography (also called "secret key cryptography") uses a single shared key between all parties. To make a 19th-century mailing parallel, this is like sending mail in a locked box where both the sender and recipient need identical copies of the box's key to send or receive mail.

Asymmetric cryptography (or "public key cryptography") employs key pairs consisting of a public key (freely shareable) and a private key (kept secret). This resembles wax-sealing envelopes—only you need to own the seal, while anyone can verify a sealed envelope by knowing your seal's shape.

The main advantage of asymmetric cryptography is that you never have to share any secret. However, it comes with limitations that make using symmetric cryptography mandatory for most use cases.

Why Symmetric Cryptography Dominates Real-World Applications

Despite the key distribution challenge, symmetric algorithms offer compelling advantages that make them indispensable:

- Compact key sizes: Typically 128-256 bits for strong security

- High performance: Orders of magnitude faster than asymmetric alternatives, making them ideal for protecting real-time data streams

- Battle-tested reliability: Built on well-understood mathematical foundations with algorithms that are well-studied and based on proven constructs

- Quantum resistance: Most symmetric algorithms remain secure against quantum computing threats, making them more future-proof than current asymmetric approaches

These benefits explain why symmetric cryptography is used more or less everywhere cryptographic security is required, including in common use cases throughout the software development lifecycle.

Common Symmetric Cryptography Algorithms and Their Applications

Understanding the landscape of symmetric cryptography algorithms is crucial for making informed implementation decisions. The most widely adopted algorithms each serve specific use cases based on their performance characteristics and security properties.

AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) remains the gold standard for symmetric encryption, offering three key sizes: AES-128, AES-192, and AES-256. AES-256 is particularly important in enterprise environments due to its quantum resistance properties. Modern implementations like AES-GCM combine encryption with authentication, providing both confidentiality and integrity in a single operation.

ChaCha20 has gained significant traction as a stream cipher alternative, especially in mobile and IoT applications where AES hardware acceleration isn't available. Its software-based implementation often outperforms AES on devices without dedicated cryptographic hardware.

Legacy algorithms like DES and 3DES should be avoided in new implementations due to known vulnerabilities. However, understanding their limitations helps developers recognize and remediate legacy systems that may still rely on these deprecated standards.

When selecting algorithms, consider factors like hardware acceleration support, key size requirements, and compliance standards. For most modern applications, AES-256-GCM provides an excellent balance of security, performance, and widespread support across cryptographic libraries.

Symmetric Cryptography in the Wild: Three Essential Use Cases

Ephemeral Session Keys: The TLS Success Story

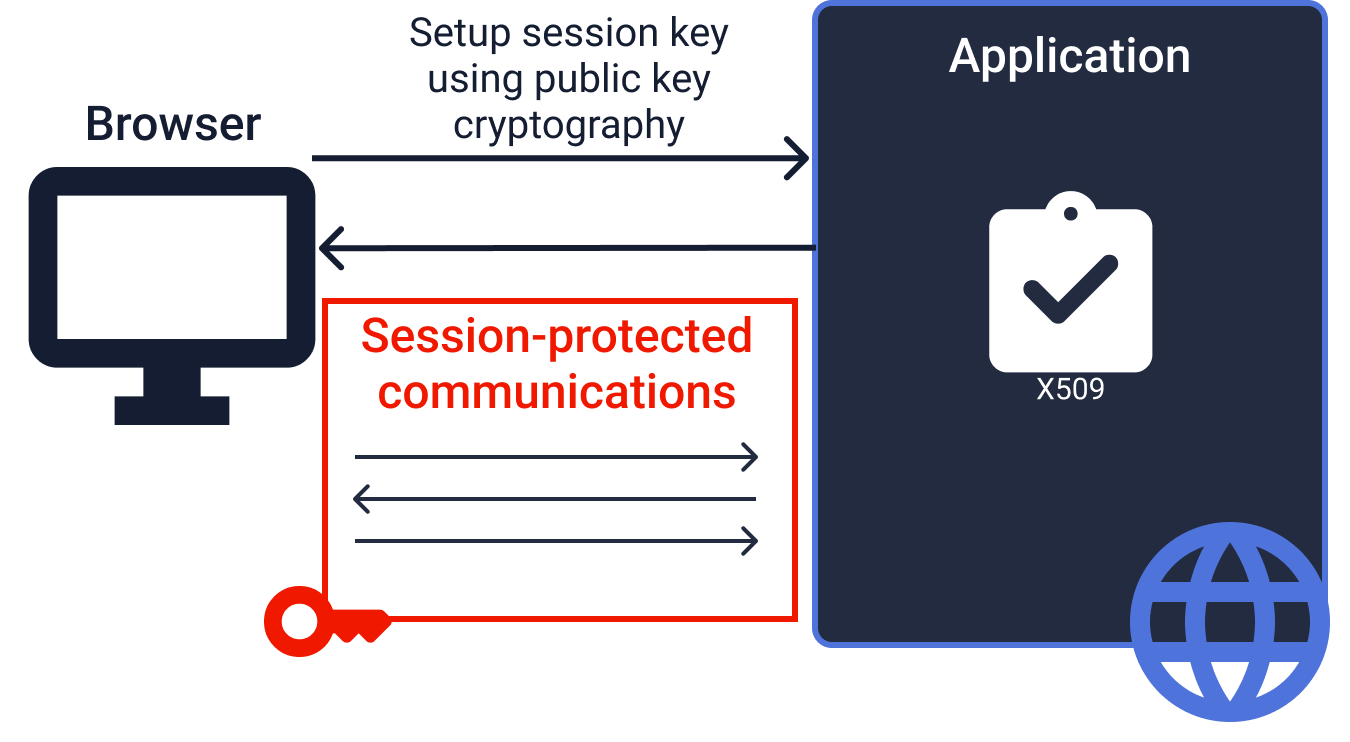

Every HTTPS request you make relies on symmetric cryptography. When your browser connects to a website, the TLS protocol establishes temporary symmetric keys called session keys. These keys encrypt all subsequent communication between your browser and the server.

Consider this TLS 1.3 cipher suite: TLS_AES_128_GCM_SHA256

This cipher suite uses AES_128_GCM as the symmetric encryption algorithm. Of course, AES in this context doesn't rely on pre-shared keys. Instead, the secret keys used in this process are called session keys—transient, ephemeral secrets that are:

- First exchanged using asymmetric mechanisms during the TLS handshake

- Used to encrypt and authenticate all data in the session

- Automatically destroyed when the communication ends

This approach combines the security benefits of asymmetric key exchange with the performance advantages of symmetric encryption for bulk data protection.

Self-Contained Applications: When You're Your Own Best Friend

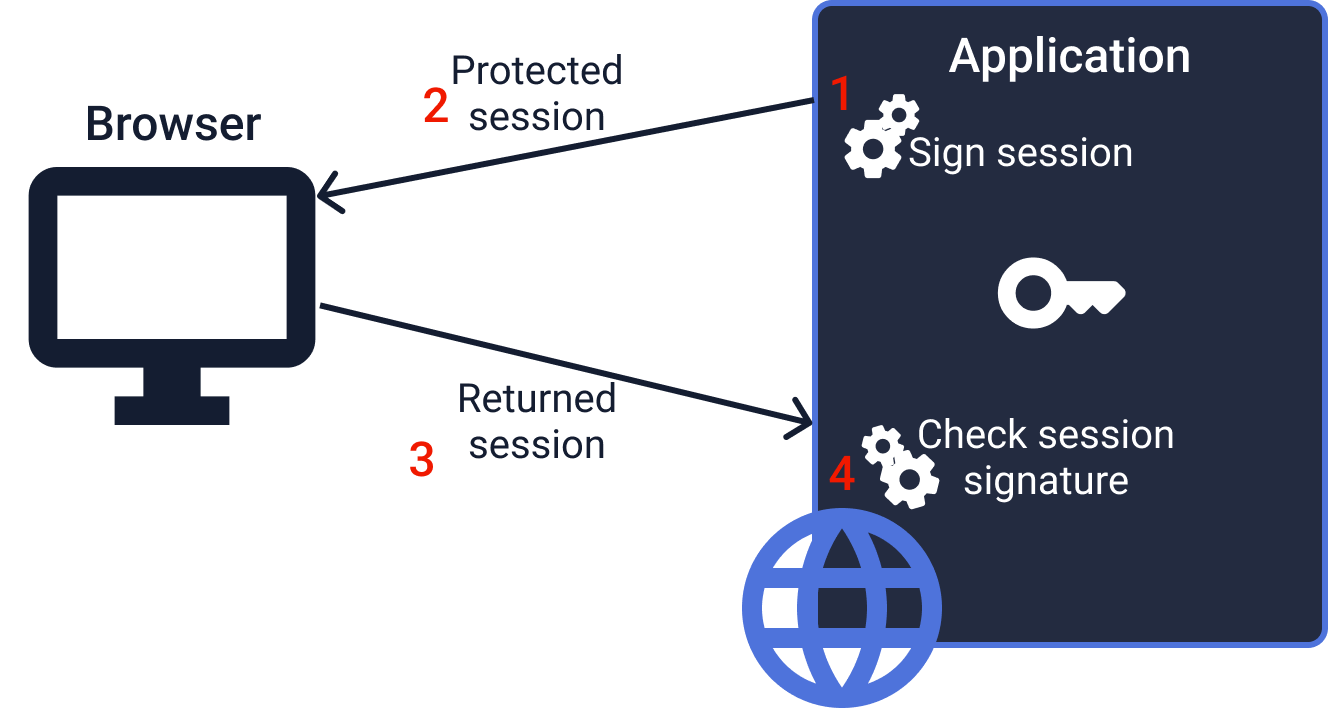

Modern web applications frequently use symmetric keys to protect data intended for internal use only. Since the application both creates and consumes this data, no external key exchange is required—the application is both the sender and receiver of the protected information.

JWT Authentication Tokens

A typical example is JWT tokens used during user authentication and authorization. These tokens store information related to the user's session, identity, or permissions and are stored on the client side. JWT tokens transmit session information from the application to itself without requiring server-side storage.

Because the browser is an untrusted communication channel where the client could modify the data, JWT includes a signature that guarantees the token's integrity. In the most common, simple use cases, these signatures are computed using a symmetric Message Authentication Code (MAC) algorithm.

The application stores the secret used to sign and verify token authenticity, but this secret doesn't need to be shared with any other party—it's purely for self-use.

Application Configuration Keys

Another example of self-use keys would be application configuration keys, like Laravel's APP_KEY. These keys are used to encrypt sensitive configuration data, cookies, session information, and other application secrets that need protection but remain within the application's control.

Hardware-Constrained Environments: When Simplicity Wins

Symmetric keys can also be used between two parties, though this is less common due to the key exchange problem. However, specific scenarios make this approach sensible, particularly in constrained environments or for hardware-level security applications.

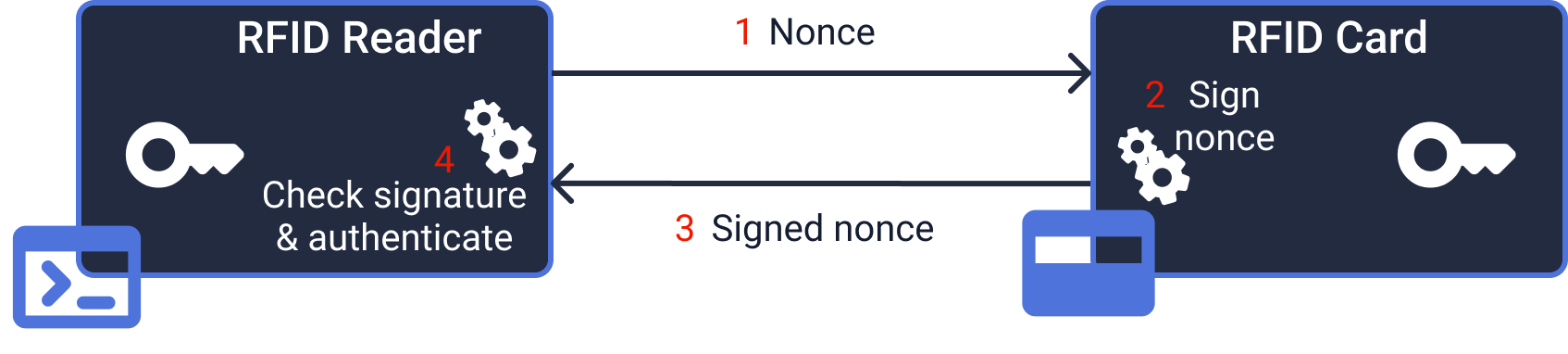

Smart Card Systems

A prime example is the interaction between an RFID smart card reader and the smart card itself. When you present your smart card to a reader (e.g. for secure login), a symmetric key is often pre-provisioned on both the card and the reader during manufacturing or personalization.

This key establishes a secure, encrypted channel for authentication and data exchange between the card and reader. This approach is highly efficient for devices with limited processing power and memory, where the overhead of asymmetric cryptography would be prohibitive, as is the case with low-power RFID applications.

However, this approach should be considered only when asymmetric alternatives are truly impractical, as it introduces significant key management challenges.

Symmetric Cryptography Security Vulnerabilities and Attack Vectors

While symmetric cryptography algorithms themselves are generally robust, implementation vulnerabilities and operational weaknesses create significant attack surfaces that developers must understand and mitigate.

Key reuse attacks represent one of the most critical vulnerabilities in symmetric cryptography implementations. When the same key encrypts multiple messages, especially with stream ciphers or certain block cipher modes, attackers can exploit patterns to recover plaintext or keys. This is particularly dangerous with initialization vector (IV) reuse in modes like CBC or CTR.

Side-channel attacks target the physical implementation rather than the mathematical algorithm. Timing attacks analyze encryption/decryption duration variations, while power analysis attacks monitor electrical consumption patterns during cryptographic operations. These attacks can reveal key material even from theoretically secure algorithms.

Weak key generation remains a persistent vulnerability. Predictable random number generators, insufficient entropy sources, or deterministic key derivation can make even strong algorithms vulnerable to brute-force attacks. The infamous Debian OpenSSL vulnerability demonstrated how implementation flaws can reduce effective key space dramatically.

Padding oracle attacks exploit error messages in block cipher implementations to gradually decrypt ciphertext without knowing the key. Proper error handling and authenticated encryption modes like GCM help mitigate these risks.

Understanding these attack vectors enables developers to implement defensive measures and choose appropriate cryptographic modes and libraries.

Symmetric vs Asymmetric Cryptography: Performance and Use Case Analysis

The fundamental differences between symmetric and asymmetric cryptography extend beyond key management to encompass performance characteristics, computational requirements, and optimal use case scenarios that directly impact system architecture decisions.

Performance differentials are substantial: symmetric algorithms typically operate 100-1000 times faster than their asymmetric counterparts. AES encryption can process gigabytes per second on modern hardware, while RSA operations are measured in thousands of operations per second. This performance gap makes symmetric cryptography essential for bulk data encryption, real-time communications, and high-throughput applications.

Computational resource requirements also differ significantly. Symmetric operations require minimal CPU cycles and memory, making them suitable for resource-constrained environments like embedded systems and IoT devices. Asymmetric operations demand substantial computational power, limiting their practical use to key exchange and digital signatures rather than bulk encryption.

Hybrid cryptosystems leverage both approaches strategically: asymmetric cryptography establishes secure key exchange, while symmetric cryptography handles actual data protection. This combination appears in protocols like TLS, where RSA or ECDH establishes session keys, and AES encrypts the communication payload.

Mastering Key Lifecycle Management

Session Keys: Letting Protocols Handle the Heavy Lifting

Session keys benefit from being embedded within established protocols like TLS. When you use a proven cryptographic library, the protocol handles key generation, exchange, rotation, and destruction automatically—working like a black box where keys are exchanged, used, renewed, and destroyed following the protocol design.

If you rely on a proven protocol and don't implement it yourself (which is considered best practice for all cryptography-related tasks), you generally don't need to worry about the symmetric keys themselves.

The Critical Logging Pitfall

Your primary responsibility is preventing accidental key disclosure. The most important point when dealing with session keys is ensuring the application doesn't log them. Leaking session keys can be particularly damaging as it enables "store now, decrypt later" attacks where adversaries capture encrypted traffic and decrypt it later using leaked keys.

Here's a dangerous Python example showing how session key logging can happen:

from OpenSSL import SSL

import logging

import socket

def verify_cb(conn, cert, errnum, depth, ok):

# Do certificate validation

pass

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

logging.basicConfig(filename='application.log', encoding='utf-8', level=logging.DEBUG)

ctx = SSL.Context(SSL.TLSv1_2_METHOD)

ctx.set_verify(SSL.VERIFY_PEER, verify_cb)

# This callback logs every session key - a security disaster

ctx.set_keylog_callback(lambda con, key: logger.debug(key))

sock = SSL.Connection(ctx, socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM))

sock.connect(("somehost.local", 443))

sock.do_handshake()Running similar code in production would result in keys being logged to the filesystem:

DEBUG:__main__:b'CLIENT_RANDOM 2f45cf41aea594d66b32ed8921ee2b4530e075f40cb611d3f01be867bdb46ef5 3bb4182a358c4f36693e848c62ce7663cf30237634259a4ea47e651a6d30c7a8c11749ccf0c52630114b9b3b1a72937b'In general, having debug features active in production is considered bad practice. Applications should avoid activating debug output in production environments to prevent information leaks in log files, which could include sensitive cryptographic keys.

Self-Use Keys: Balancing Security and Operational Continuity

Similar to session keys, self-use keys aren't generally shared with external parties, simplifying the key management problem to a degree. However, because these keys are long-lived and directly tied to application functionality (like signing JWTs or encrypting configurations), their secure handling throughout their lifecycle is crucial.

The primary concerns for self-use keys revolve around their generation, storage, and rotation.

The Ephemeral Key Strategy

For a better security posture, it's often beneficial to avoid storing self-use keys altogether. Instead, consider generating them dynamically at application startup. The primary benefit of this method is that keys never exist in persistent form.

Instead of storing the key in environment variables, configuration files, or databases, the key is created each time the application starts, ensuring it only exists in memory for the duration of the application's runtime. This reduces the chance of accidental exposure, whether from system compromise, debug logs, or misconfiguration.

Since the key is only generated and used within the application's session, it's ephemeral and tied directly to the application instance. Once the application stops or restarts, the key is discarded and regenerated, ensuring no sensitive information persists beyond the runtime.

Implementing Graceful Key Rotation

While the ephemeral approach offers the best security, it comes with limitations. Regenerating the key at each startup can challenge applications requiring continuity.

Relying on a fallback mechanism to accept older keys for some time while using new keys to protect fresh data can solve this problem. This is best illustrated by Django's SECRET_KEY_FALLBACKS mechanism:

from pathlib import Path

import os

# Build paths inside the project like this: BASE_DIR / 'subdir'.

BASE_DIR = Path(__file__).resolve().parent.parent

# Quick-start development settings - unsuitable for production

# See https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/5.2/howto/deployment/checklist/

# SECURITY WARNING: keep the secret key used in production secret!

SECRET_KEY = os.environ["DJANGO_SECRET_KEY"]

if "DJANGO_SECRET_KEY_FALLBACK" in os.environ:

SECRET_KEY_FALLBACKS = [os.environ["DJANGO_SECRET_KEY_FALLBACK"]]

# [...]In this configuration, the application uses the DJANGO_SECRET_KEY environment variable to issue all future cryptographic signatures. The second variable, SECRET_KEY_FALLBACKS, is used only for signature verification and corresponds to the rotated key value. This ensures continuity of previous signatures while allowing more frequent key rotation.

Key Rotation Security Considerations

Only a few security considerations remain when implementing this approach:

- Limit fallback keys to a low number: Never cleaning the values in the fallback key list defeats the purpose of key rotation

- Time-bound fallback key usage: Rotated keys should only verify or decrypt data that could have been issued before the rotation. Generally, rotated keys are no longer needed after some time - for example, when all user sessions have reached expiration

- Clean all keys when compromised: When there's doubt that one of the keys could have leaked, clean all keys and restart with only a fresh key and no fallbacks. This will invalidate any previously protected data, but is necessary to restore application security

Pre-Shared Keys: The Last Resort Option

Pre-shared keys (PSKs) are symmetric cryptographic keys shared between two parties before any communication begins. Unlike session keys, which are typically exchanged dynamically as part of a protocol, PSKs are manually distributed or configured in advance.

This makes PSKs suitable for environments where key exchange is impractical or where parties need to establish secure communication without the overhead of dynamic key exchange protocols.

When PSKs Make Sense

In general, relying on PSKs for security should be discouraged and used only as a last resort or for specific environments. For most use cases, it's often possible to rely on higher-level cryptographic protocols or hybrid cryptosystems (as seen in GPG).

Pre-shared keys should generally only be considered in:

- Disconnected infrastructure: Environments lacking network connectivity for dynamic key exchange

- Computationally constrained devices: When some parties lack the computational power required to execute asymmetric algorithms

Hardening PSK Implementations

In such environments, the challenge is generally high. Apart from the key distribution problem, the lack of device connectivity often implies that keys cannot be rotated or regenerated, as a new key exchange wouldn't be possible. Using such very long-term keys comes with additional security requirements:

Enhanced Key Storage Protection: PSKs must be stored securely to prevent unauthorized access. This involves using Hardware Security Modules (HSMs) or other hardware secure elements that protect the key from extraction, even if a party is physically compromised.

Strong Key Generation: A robust and cryptographically secure method must be used to generate the PSK. Relying on weak or predictable keys makes it easier for attackers to guess or brute-force the key. High-entropy, random key generation is essential to ensure the security of long-term PSKs.

Future-proof algorithms and key lengths: Relying on secure, proven algorithms when using long-term PSKs is paramount. It's not possible to move away from a broken algorithm in such use cases. Good options include:

- Encryption: AES-256 using state-of-the-art modes of operation

- Authentication: HMAC-SHA-512 for signatures

Note that these algorithms require different key sizes, which also need to be accommodated in your key management system.

Universal Best Practices for Symmetric Key Management

Whichever type of symmetric key you use, and whether or not you choose to dynamically manage your self-use secrets, follow these fundamental cryptographic best practices:

Secure Key Generation

Generate all keys securely using cryptographic random generation. Any key used for cryptographic purposes should be generated securely using cryptographically secure random number generators. Most operating systems provide secure generation mechanisms, such as Linux's /dev/urandom, which are also usually wrapped inside frameworks' utility functions.

Single-Purpose Keys

Use one key for one purpose. If you need to encrypt and sign data, it's generally recommended to use two different keys. It's also possible to derive two keys from a single master key using strong secret diversification methods. This prevents unexpected and complex side effects that depend on the cryptographic algorithms and can have catastrophic consequences.

Aggressive Key Rotation

Rotate your keys as often as possible. Machines have no problems remembering new secrets—you can generate new keys every week or day without issue on their side. Short key expiration means:

- Less time for an attacker to exploit a leak

- Fewer chances to overflow the maximum call numbers per key of a cryptographic algorithm

- Regular opportunities to improve security practices

Secure Storage Solutions

Avoid storing your keys in plain files. If you need to store your keys long-term, prefer using a secret vault rather than plain files. This makes both leaking the secret and exposing it through an application vulnerability more difficult.

Consider these options:

- Cloud providers: AWS Secrets Manager, Azure Key Vault, Google Secret Manager

- Open source: HashiCorp Vault, Kubernetes Secrets

- Hardware: HSMs for high-security requirements

Comprehensive Secret Detection

If you rely on a secret detection solution to be notified of secret key leaks, ensure you use one with strong support for generic secrets. Symmetric keys usually don't follow recognizable patterns and are thus more difficult to detect than most API keys.

Generic secret detection requires more sophisticated entropy-based analysis and pattern recognition to identify potentially leaked symmetric keys in code repositories, logs, and configuration files.

By following these practices, you'll build robust systems that leverage symmetric cryptography's performance benefits while maintaining strong security postures throughout the key lifecycle.

FAQ

What are the most secure symmetric cryptography algorithms for modern applications?

For most enterprise and cloud-native environments, AES (especially AES-256-GCM) is the gold standard due to its strong security, performance, and quantum resistance. ChaCha20 is also recommended for software-only or mobile/IoT scenarios lacking hardware acceleration. Legacy algorithms like DES and 3DES should be avoided due to known vulnerabilities.

How should symmetric keys be generated and stored to minimize risk?

Always use cryptographically secure random number generators for key creation. Store long-term keys in dedicated secret vaults (e.g., HashiCorp Vault, AWS Secrets Manager, HSMs) rather than plain files or environment variables. For ephemeral or session keys, rely on established protocols and avoid logging or persisting them.

What are the main operational risks associated with symmetric cryptography?

Key reuse, weak key generation, and improper storage are primary risks. Reusing keys across multiple messages or using predictable keys exposes systems to cryptanalysis. Side-channel and padding oracle attacks can also compromise keys if implementations are not hardened. Regular rotation and robust detection mechanisms are essential.

When is it appropriate to use pre-shared keys (PSKs) in production systems?

PSKs should only be used in environments where dynamic key exchange is impractical, such as disconnected infrastructure or highly resource-constrained devices (e.g., smart cards, IoT). In these cases, ensure strong key generation, secure hardware storage, and plan for infrequent but mandatory key rotation when feasible.

How does symmetric cryptography compare to asymmetric cryptography in terms of performance and scalability?

Symmetric cryptography is orders of magnitude faster and less resource-intensive than asymmetric approaches, making it ideal for bulk data encryption and real-time communications. Asymmetric cryptography is best suited for key exchange and digital signatures. Hybrid protocols (e.g., TLS) combine both for optimal security and efficiency.

What best practices should security teams follow for symmetric key lifecycle management?

Implement aggressive key rotation, use single-purpose keys, and leverage secure storage solutions. Avoid logging or exposing keys in application output. For self-use keys, consider ephemeral generation or fallback mechanisms for seamless rotation. Always monitor for leaks with advanced secret detection tools that support generic symmetric keys.