About this series

Last time, a developer at Poor Corp was looking for a GitHub Action to interact with their Jenkins server, and they ended up using a malicious action that was published by a cyber-criminal. The criminal dressed up the action to be helpful looking in order to entice victims, but when the action would run, it would steal secrets from the victims’ environments. Poor Corp ended up getting deployment keys stolen, and the malicious hacker racked up a massive bill in Poor Corp’s cloud provider account.

Most stories in this series talk about the actions of black hat hackers, but today we are changing up the scenario and telling a story about a white hat hacker who saved the day.

Finding leaked code

It begins with a strange email that was sent to all of Poor Corp’s publicly listed email addresses. The email contained a vague message stating that the sender had found a security vulnerability and needed Poor Corp to reach out to them immediately.

Unfortunately, none of the addresses that received this email were the information security team, and there were mixed reactions from those who did receive the email. Some of the recipients ignored the message because it had nothing to do with their job. Others thought it was spam and deleted it. Luckily, a single employee at Poor Corp submitted it to the security team for review because they thought the email might be a phish.

When Poor Corp’s security team saw the email, they decided to reach out to the sender, who identified themself as a bug bounty hunter. The white hat hacker said that they had found Poor Corp’s code on GitHub and that it appeared to contain API keys. Initially, Poor Corp’s security team was confused. They used GitHub, but they had locked down their organization’s policy to not allow public repositories. When the white hat hacker sent them the link to the code they had found, it started to make more sense. The repository wasn’t in Poor Corp’s GitHub organization. It was published by an individual, and this individual was a software engineer at Poor Corp. After reaching out to the engineer, it became apparent that this was an accident.

How the code was leaked

To understand how this happened, we need to take a step away from our story for a moment and explain some things about GitHub. Unfortunately, due to the way GitHub has architected its enterprise/organization offering, accidentally leaking code is not only impossible for organizations to prevent, but it's also an easy mistake for developers to make.

When a business sets up a GitHub Enterprise account, its developers join the organization with a “personal” GitHub account. It doesn’t matter if the employee created a company-specific account or used their personal one; the business has no control over that individual account because, as of now, there is no straightforward way to set up managed accounts on GitHub.

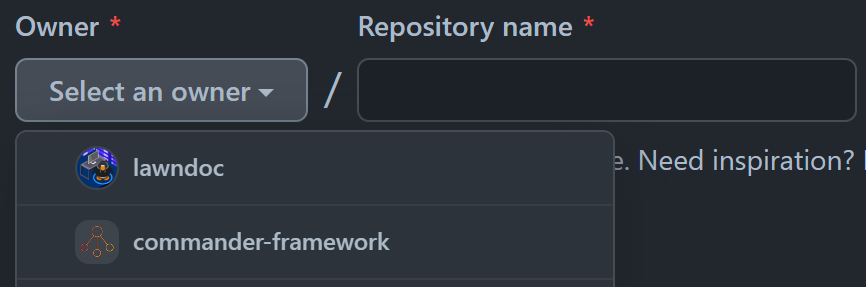

When you create a new repo in GitHub, you have a drop-down menu to select the owner of the repo. Your own username is an option, and so is any organization you are a member of.

When a repo is owned by an organization, there may be policies put in place by the organization that can make restrictions like not allowing a repo to be public. However, when you create a repo in your own account’s ownership, that is considered a “personal” repo. Your business’s policies cannot restrict or change any settings in repos owned by your personal account. Additionally, personal repos are public by default.

Going back to Poor Corp’s story, the information security team found out the full story after talking to their software engineer. The software engineer had gone to publish some Poor Corp code on GitHub, and when he did it, he accidentally selected his own username as the owner of the repo and left the default visibility in place (public). A couple of days later, the white hat hacker had been searching GitHub for hard-coded secrets when they found the leaked repo and the API key inside.

In addition to unraveling the story, Poor Corp revoked the API key, checked their logs to ensure it hadn’t been used, and rewarded the bug bounty hunter for reporting the leaked code to them. After the incident was wrapped up, Poor Corp educated their other developers about the newly discovered danger and took steps to detect secrets in their other repos.

Lessons learned

The first takeaway from this story is the trouble that the white hat hacker had to go through to get in touch with Poor Corp’s security team. In fact, the email may have never even reached them if their employee hadn’t thought it was a phish and made it visible to them. Had they not discovered the API key and their leaked code could have been found and abused by a malicious hacker.

With that in mind, we can clearly see the importance of making your security reporting process as easy and visible as possible. Make sure your websites have a security.txt file that includes a way to contact your security team. Also, ensure that you have some sort of security reporting process published on your public GitHub and social media accounts.

The bigger takeaway from this story is highlighting how easy it is to accidentally leak your company’s code on GitHub. GitHub’s cloud service doesn’t allow for managed accounts, so you are always a simple mistake away from putting your organization’s code out of their control and into public view. Worst of all, there is no way for organizations to prevent this other than by educating their developers on what not to do.

Because of the severity and likelihood of this vulnerability, I want to point you to a tool that can help you detect leaked code.

- One is an app I developed to be published alongside this blog post: https://github.com/lawndoc/github-leak-audit. The app uses GitHub’s API to monitor all your GitHub organization members’ personal public repos for potential leaks. It is specifically targeted for the accidental leak scenario described in this blog post. It will detect previously unknown code and new repos. To set it up in your organization, you’ll need to fork the repo under your organization’s ownership, set up a GitHub app or PAT secret for it, and enable the GitHub Actions workflow. Detailed instructions are in the README.

Views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official policy, position, or views of GitGuardian, The content is provided for informational purposes, GitGuardian assumes no responsibility for any errors, omissions, or outcomes resulting from the use of this information. Should you have any enquiry with regard to the content, please contact the author directly.